Back to Life, Positively 2020 Index…

A headline in the July 3, 1981 issue of The New York Times read “Rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals.” An advertisement for Independence Savings Bank featured a cut-out with the lyrics of “The Star-Spangled Banner” to the story’s right. This first mainstream news article about the disease, which would later become known as AIDS, or Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, was an early warning call to gay communities across the country.

Kevin Melody remembers that story. He and his partner, Ricky Carswell, lived in Valdese, a small town in Burke County where it took a few days to get the paper delivered. The two met in 1976. Melody was living in Morganton and working as a union organizer for the United Auto Workers. Organized labor made some headway in the second half of the 20th century in North Carolina and activities increased in the state’s agricultural and food-processing industries nearing the 1990s. Melody was one of those early organizers to help agricultural workers at a poultry plant in Morganton.

“At a party for some of these agricultural workers, that’s where I met him,” says Melody. “He was a country boy,” referring fondly to Carswell. After years in small towns, the two moved to Charlotte in 1983. The Morganton plant had shut down and Carswell got a job at a local travel agency. Charlotte was like a breath of fresh air.

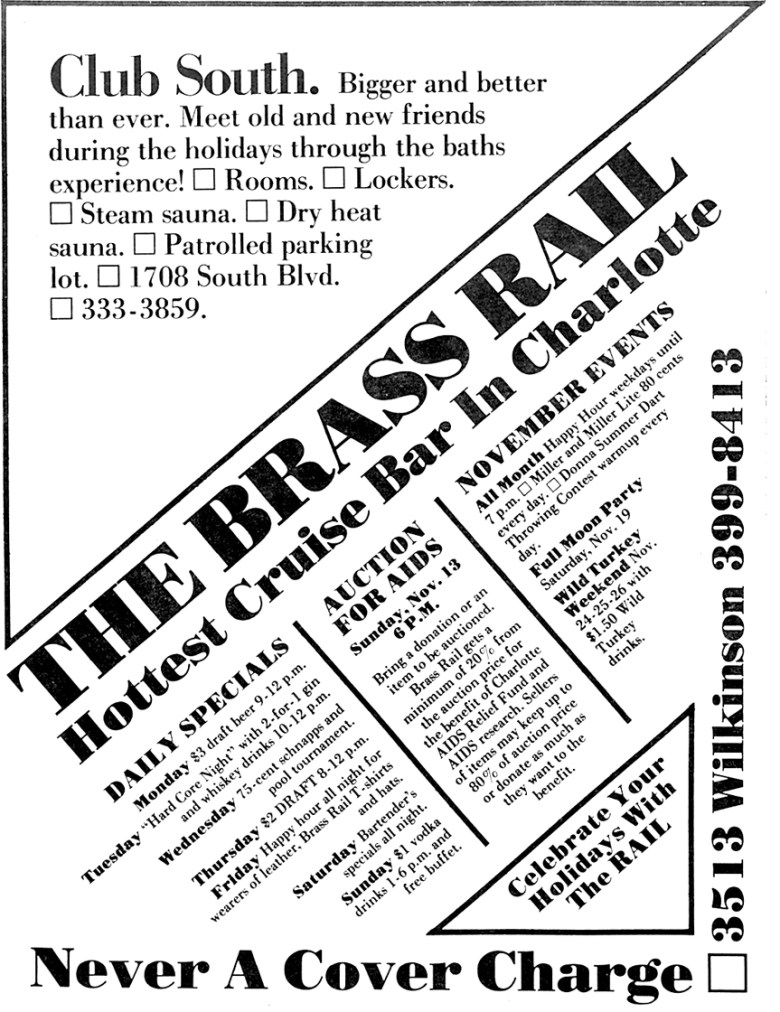

According to Greg Brafford, “Charlotte was a wild city.” While the city has a less-defined gay nightlife today, in the mid-1980s it had eight or nine gay bars and two bathhouses. Brafford was the owner and manager of O’leens and the Brass Rail. Bars were an essential part of peoples’ lives at the time, often providing a refuge from harassment in the rest of the city or from families who weren’t supportive.

The gay community, like Brafford, Carswell, Melody and hundreds more, didn’t realize how the disease was about to impact their lives.

The First Cases

The first cases in Charlotte were just a few years away. According to a story in qnotes from 1983, Chris Lemmond, Hugh Gagner and Kevin Jochems formed the Charlotte AIDS Relief Fund (CARF) following the death of their friend Nat Strickland. At the time there were essentially no funds available to help AIDS victims with expenses. The nightclub, Scorpio, held a fundraiser for CARF and the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, which was leading national programs for gay men diagnosed with AIDS. Brafford’s Brass Rail held an AIDS auction that month to benefit the fund as well. At the time, there were 20 reported cases in North Carolina.

Melody remembers the years to follow as a very rough time. Without any treatment, “the death rate was almost 100 percent fatal,” he recalls. In 1985, six gay men in Charlotte, including Les Kooyman and his partner Sandy Berlin, founded the Metrolina AIDS Project (MAP), the second such organization in the Southeast. Melody and Carswell started volunteering shortly thereafter. The next year, Carswell was diagnosed with full-blown AIDS. “He was on a business trip in Atlanta and he got really sick,” remembers Melody.

That year, North Carolina reported 232 cases and 145 deaths as of June 1986. Melody organized the AIDS Hotline for MAP and the two volunteered in the organization’s “Buddy” program. According to early literature, “A ‘buddy’ works directly with a person who has AIDS, ensuring that essentials are taken care of, buying groceries, mowing the lawn, providing transportation, contacting doctors or social service agencies, or just listening and being a friend.”

There were only five doctors in Charlotte at the time who would see people who showed symptoms. The phone line, which operated five nights a week, was the only place for information for a while. According to Melody, they had about 20 volunteers working out of an office on East 5th St. in Charlotte. After getting a grant from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), MAP’s hotline started taking calls from across the Southeast United States. “Over half of the volunteers were HIV positive,” says Melody. He describes the difficulty in trying to offer a little bit of hope when so many around him were getting sick. “All of our friends started testing positive…just about everybody I knew,” he says.

A Lost Generation

Brafford remembers when AIDS started increasing in the Charlotte gay community. “People just started dying of pneumonia,” he says. “These were young 20-year-old people dying.” Brafford describes it as a time when there was also no help coming from anywhere. MAP was the first organization to locally start giving out information to keep the community safe, and they had no funding.

“The next 10 years, we lost so many people,” says Brafford who says he saw 20 employees and over 500 customers die of AIDS in the next decade. The bars, which were the center of gay life at the time, started giving out information about AIDS and having fundraisers to support the work of MAP, help individuals, and even pay for cremation. Brafford remembers the endless amount of time that drag queens gave to raise money and the support that came from the lesbian community. There were even underground networks to help recycle medications. “The medicine was so scarce and so expensive,” says Brafford. There were no federal programs, like today’s Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program to support people. “A lot of things went on like that … almost nobody lived after they were diagnosed.”

He remembers people coming together to try and do the most they could do in such a difficult time. “It was our shining moment,” says Brafford while fighting back tears. “Almost all the bars did some form of education and some form of benefits — all of it was to help MAP.”

Melody and Carswell felt the same way. “We could do something and not just be victims,” remembers Melody. Even in hospitals, many nurses balked about working with AIDS patients and he remembers food service staff who wouldn’t even deliver trays to the rooms. “They’d just leave it outside the door,” says Melody.

They lost their first close friend in 1989. Melody remembers it being the year that Hurricane Hugo came through. The next six years would continue in much the same way. The mortality rate increased between 1990 and 1996 in Charlotte. “I was constantly going to funerals,” he says and remembers sometimes losing a friend every day. On top of that, he was taking care of Carswell. After their best friend died in 1993, Carswell thought of taking his own life. Between 1987 and 1995, over 250,000 people had died from AIDS in the United States.

Carswell found support from Father Conrad Hoover and Father Gene McCreesh who would visit him once or twice a day. Melody describes their life as fairly normal until the early 1990s when Carswell started getting sicker. “He would have bouts where he was really healthy and then once in a while he’d get sick,” he says. Carswell died on Nov. 6, 1994.

Melody, who is 70 years old, doesn’t have a lot of friends his own age. So many of them died. “Sometimes if I just think about it a little bit, I’ll tear up,” he says. “But I don’t want to forget and I really don’t want to put it all past me.” The AIDS epidemic showed the community at large the humanity of gay people. It created organizations that support LGBTQ causes today, made people think about pre-existing conditions in healthcare, and even impacted the fight for marriage equality years later, but as Melody points out, “it changed a lot of people’s view of us — unfortunately, we had to pay a really high price for that.”

One of the last things that Carswell said to him was “Don’t forget us.” He wasn’t talking about himself, but about the thousands lost to the disease. “Don’t forget our stories. Don’t forget what we went through because if we’re going to be remembered at all, we’re only going to be remembered through you.” Melody’s been trying to do his best to do that ever since.

Join us: This story is made possible with the help of qnotes’ contributors. If you’d like to show your support so qnotes can provide more news, features and opinion pieces like this, give a regular or one-time donation today.